An Asterism and a Planetary Nebula

February 2021 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

For this feature, I try to restrict myself to objects that culminate within about an hour of midnight (UT) during the month in question. Sometimes, as this month, this puts serious restrictions on what is visible. February is a poor month for open clusters. The NGC lists only six clusters north of -30° declination within these parameters.

Three of these objects are in Cancer and two are very famous, M44 (or Praesepe) and M67. The third object lies close to M67 and is, I’m afraid, a bit of an imposter.

It lies 34’ south-west of the centre of M67 and was first observed (as ever) by William Herschel on 15th March 1784. He entered it as number 10 in his category VIII (coarsely scattered clusters of stars). His description reads A cluster of very coarse scattered stars. Not rich.

His son, John Herschel, put four observations of it in his 1833 catalogue, where it appears as no. 528. His descriptions show that he was uncertain of the reality of the cluster. The first two observations were made in 1828 and read The chief star 9 or 10 magnitude of a place rich in stars

and An insignificant cluster. No other near.

The first observation simply defines the location he gives for the entry, but it’s interesting that he calls it 'a place rich in stars' rather than 'a cluster'. The second observation sounds like he’s thinking 'Am I looking in the right place? There’s no other cluster nearby, so maybe I am.'

The other two observations, from 1830, both use the word 'cluster', but are not enthusiastic: A very coarse and poor cluster…

and A poor cluster of 4 or 5 large and a few scattered small stars.

In 1888, the object made its way into the NGC as no. 2678, bearing the uninspiring description Cluster, very little compressed, poor.

John Herschel’s final description is an accurate summary of what is seen in the eyepiece. If it wasn’t for the presence of the 4 or 5 bright stars, there is nothing here that would draw the eye.

Most authorities now list NGC 2678 as an asterism, but there are still several (particularly online) that list it as an open cluster.

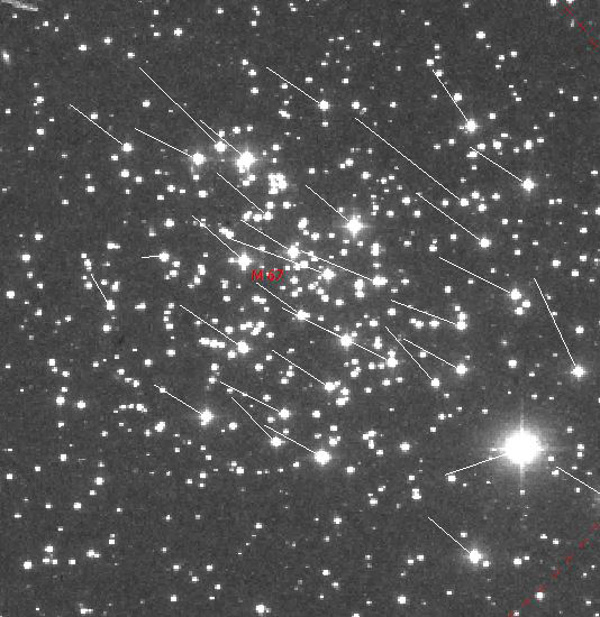

One of the defining features of a true open cluster is that its member stars are all travelling more-or-less in the same direction and at the same speed. They are, after all, gravitationally linked to each other. Here, for example, is an image of nearby M67 with lines added to indicate the stars’ proper motions over the next 100,000 years.

The stars are clearly all travelling in pretty much the same direction and at the same speed. Those whose proper motion vectors are significantly different are not, therefore, members of the cluster.

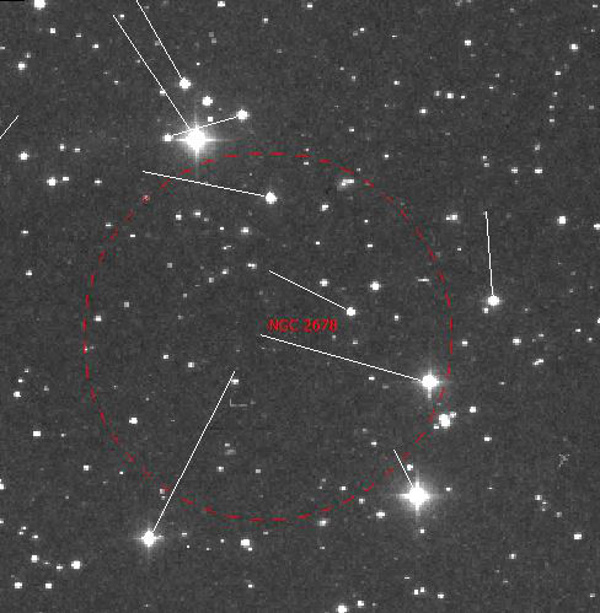

Now let’s have a look at NGC 2678 in an image to the same scale.

As you can see, the bright stars have almost no commonality of direction or speed, certainly not enough to identify this 'place rich in stars' as an open cluster. It’s an asterism.

Turning to a more real object, our nebula for this month culminates at midnight on 31st January. From the centre of the British Isles, it only attains an altitude of 20° and thus may be problematic for observers in light-polluted areas (which is most of us, I know).

NGC 2610 is a planetary nebula in Hydra. Its declination of -16°, its faintness (around 13th magnitude) and the fact that it lies in a rather barren patch of sky (the nearest bright(ish) star is the 4.9 magnitude 9 Hya, 2° to its east) make it a less than popular target for visual observers in Britain. It is, however, worth seeking out if you can.

Data on this planetary nebula is difficult to come by. If we assume a true diameter of about one light-year (an average for planetary nebulae) then it must lie at a distance of around 3,500 light-years.

I offer two of my observations here to illustrate the difference latitude and aperture can make. Both were made in dark-sky sites and both were made at x150 with a 20’ field. The first was made with a 16” (400mm) Newtonian reflector from a latitude of 24°N.

Bright and easy. Initially, this object was perceived as a disc, but closer observation revealed a darker centre, giving the object a slightly elongated annular appearance.

The object was at an altitude of 49° at the time of this observation.

The second observation was made with a 12” (300mm) Newtonian from a latitude of 55°N.

Pretty difficult, even with the OIII filter in place. The low altitude of 19° didn't help. Quite large and circular. No structure seen. A brighter point was seen at the centre (but only without the OIII filter). This is unlikely to have been the central star which shines at magnitude 15.9.

The more northerly observation is reproduced below.

I’d be interested to hear of your experiences of NGC 2610. How easy or difficult is it?

| Object | RA | Dec | Type | Magnitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGC 2678 | 08h 51m 08s | +11° 15’ 20” | Asterism | Br st =8.5 |

| NGC 2610 | 08h 34m 19s | -16° 13’ 06” | Planetary nebula | about 13 |