Nebula and Cluster of the Month Archive 2025

In this series of articles we draw your attention to Nebulae, Clusters and other Galactic objects that are particularly worthly of an observer's time.

-

IC 2149 in Auriga

December 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

As the year draws to its close, I’m going to indulge myself. I make no apologies for this. You never know, I may even make one or two converts. For a long time, I have been a keen seeker of the tiny planetary nebulae, those objects usually ignored by visual observers. Why are they ignored? Because they’re very small, often indistinguishable from stars and they’re not ‘exciting’. They’re not ‘interesting’, not ‘spectacular’. My argument is that they are exciting, they are interesting and they are spectacular.

This month we’re going to look at IC 2149, a ‘stellar’ (though it’s not stellar) planetary nebula in Auriga, riding high in the December skies.

IC 2149 was discovered photographically by Williamina Fleming, a Scottish astronomer working at Harvard College Observatory, in 1906, and it entered the second Index Catalogue in 1908. The description is typically terse:

Planetary, stellar

.Multiwavelength studies of IC 2149 reveal that it does not comfortably fit a simple planetary nebula profile, but shows considerable asymmetry. Optical and radio images reveal an asymmetric object, yet with some bilateral symmetry, with a very bright, compact inner zone surrounded by fainter, more diffuse emission.1

High-resolution imaging by the Hubble Space Telescope shows a bright knot, irregular shell structures and a tenuous outer halo, all indicating a history of directionally irregular mass loss.2,3

A colour composite image of planetary nebula IC 2149 in Auriga captured by the Hubble Space Telescope with its WFPC2 instrument courtesy of the Hubble Legacy Archive. Distance estimates place IC 2149 at approximately 1.0—1.2 kpc (3200—3900 light-years) from the Sun4. At this distance, the ionised mass is small, around 0.03 solar masses, consistent with a low-mass progenitor at the end of its Asymptotic Giant Branch phase. Expansion velocities measured from optical spectroscopy show moderate values of a few tens of km/s.5,6 Radio continuum mapping reveals further structural complexity.7

The central star is a hot O-type star showing strong stellar wind signatures. Ultraviolet and optical spectroscopy reveal iron-group lines and P Cygni profiles, indicating ongoing mass loss.8

Visually, it could be argued that IC 2149 is not much to look at. If you’d indulge me, though, I’m going to ask you to search for IC 2149 visually at low to moderate power. At magnitude 10.6, it should be clearly visible, if not immediately recognisable. In discussion with other visual observers, I’ve noticed that some (not all) can spot a ‘stellar’ planetary nebula almost immediately, even if the magnification does not allow a glimpse of its extended shape.

To find the object, centre your field on β Aurigae (magnitude 1.9), on Auriga’s right shoulder. Move one degree north to the reddish, 4.3-magnitude π Aur, then just 38’ slightly north of west from π. IC 2149 should now be close to the centre of your field. I, and others, find that there is something about a planetary nebula that makes it stand out. There’s a certain quality of the light that makes it different, somehow, from the field stars. Maybe it’s because the light from a planetary nebula is not a continuum. I don’t know, and I’m sorry for being vague, but try it for yourself. For me, IC 2149 pops out almost instantly, even on lower finding powers.

Once you think you’ve got it, swap your eyepiece for a higher magnification one, and the extended nature of the object should become clear. Failing that, ‘blinking’ with an OIII or UHC filter should make the object obvious.

I’ve included an observation I made of IC 2149 back in 2013. On that occasion, I recorded that elongation was suspected at x150, and this was confirmed at x450. The middle is brighter and there is a fainter outer periphery. The object is tiny, and no further detail was visible.

A sketch of planetary nebula IC 2149 in Auriga by Patrick Maloney through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x150 magnification. May I take this opportunity to wish you a very happy Christmas season (or whichever other Midwinter celebration you choose to celebrate).

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude IC 2149 05h 56m 24s +46° 06’ Planetary nebula 10.6 References:

- Vázquez, R. et al., 2002. ‘Multiwavelength observations of the peculiar planetary nebula IC 2149’. Astrophysical Journal, 576, pp.860–870.

- ibid

- Miranda, L.F. et al., 2000. ‘High-resolution observations of bipolar planetary nebulae’. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 311, 748–760.

- as 1.

- Perinotto M. (1982). ‘Stellar wind in the nucleus of IC 2149’. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 108, 314.

- Sistla, G., 1977. ‘Extinction and radio structure of IC 2149’. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 178, pp.325–334.

- ibid

- Feibelman, W.A., 1994. ‘Spectrum of IC 2149 and its central star’. Astrophysical Journal, 426, pp.653–665.

-

NGC 1501 in Camelopardalis

November 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

Nestled in the southern reaches of the faint stars that make up the busy but often overlooked polar constellation of Camelopardalis (the giraffe - so named because it was once thought that a giraffe was the result of an unlikely cross between a camel and a leopard), lies the planetary nebula NGC 1501.

As should be expected, this was a discovery of William Herschel, who first saw it on the night of 3rd November 1787. He placed the object in his fourth category – planetary nebulae – as 53 H.IV, adding the description

A pretty bright planetary nebula near 1' diameter. Round. Of uniform light and pretty well defined. Two observations [were made] with 360[x] magnified in proportion; but still pretty abruptly defined, and a little elliptical.

The planetary nebula lies in a region of the sky surprisingly devoid of bright stars, especially considering that the Milky Way runs right through it. The closest star of any brightness is the 4th-magnitude β Camelopardalis, and that’s 7° away.

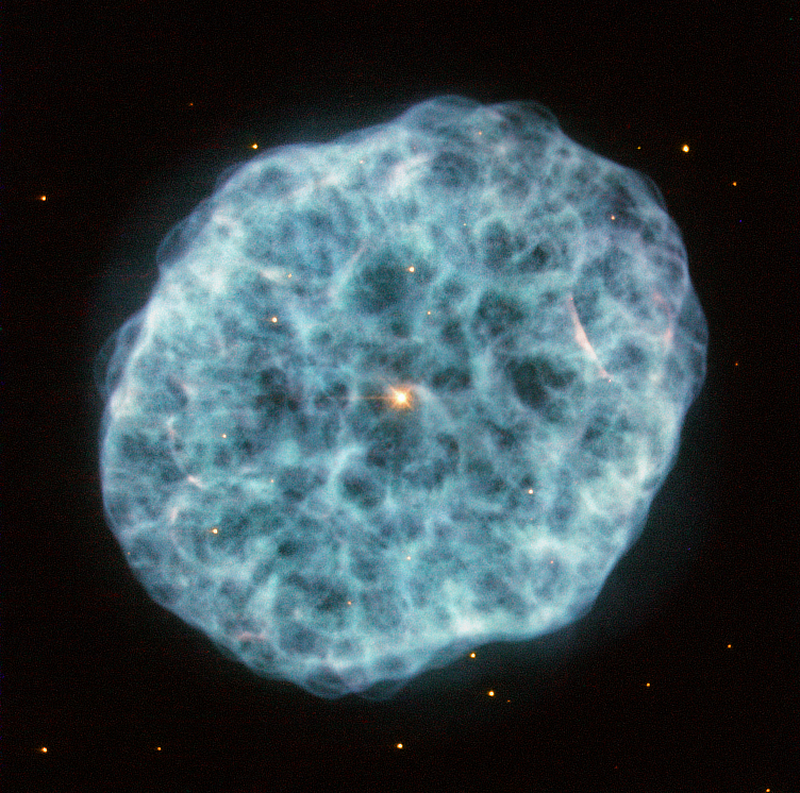

NGC 1501 has a very complex morphology. Although to the visual observer it appears as a fairly smooth and round or oval, this belies the true complexity, which can be seen in the Hubble image below. Spectroscopic and imaging studies made by Sabbadin et al in 2000 reveal that NGC 1501 is not a smooth, spherical shell but possesses numerous protrusions and lobes on an overall ellipsoidal body. The authors described it as a ‘boiling, tetra-lobed shell’.1

An image of planetary nebula NGC 1501 in Camelopardalis provided by ESA/Hubble & NASA; acknowledgement: Marc Canale. The central star bears the variable star designation CH Camelopardalis and has a spectral type of [WC4], a hydrogen-deficient, carbon-rich, Wolf-Rayet star with a surface temperature of around 100,000K. It displays multiple periodicities between 19 minutes and 87 minutes, the strongest of which are found at 31, 45, 56 and 87 minutes. Magnitude variations are typically small, ranging from 0.02 to 0.05 magnitude, but there are rapid, irregular fluctuations caused by the resonance of several close modes.2

The star has a mass of about 0.55 solar masses, a very high stellar wind, and is on the cusp of the final phase of its life; white dwarf cooling.3

To the visual observer, all of this can only be of academic interest. The nebula is fairly bright – magnitude 11.5 in most listings, but sometimes quoted (incorrectly, I think) as 13.0. It measures about 60” by 55”, but usually looks pretty round.

The central star is magnitude 14.5. Some observers say they can see it clearly with telescopes as small as 8” aperture. Others say otherwise. The observation I present here was made with my 12” Newtonian under sub-optimal conditions, and I didn’t see it, though there is a small, brighter patch in the centre.

A sketch of planetary nebula NGC 1501 in Camelopardalis by Patrick Maloney through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x150 magnification. When I made the observation, I wrote in my journal

Quite large and immediately visible to direct vision even without the OIII filter. Round. With the OIII filter it appears occasionally to be darker in the middle, possibly with two voids. Very slightly elongated.

In The Night Sky Observer’s Guide, the object is described as seen through a 12” – 14” telescope as showing the same darkening as I saw.

... The centre is slightly darker, its annularity being more noticeable at higher power.

The author goes on to say that the central star was prominent.As usual with planetary nebulae, it is worth using an OIII filter. This often brings out more detail and structure than can be seen without. Central stars should be searched for, however, without an OIII or Nebular filter, as these tend to suppress continuum emission.

NGC 1501, then, is far more than a simple glowing shell. It is a dynamic, turbulent and chemically diverse structure surrounding a complex, pulsating hydrogen-deficient star. Its study sheds light on the final stages of stellar evolution and the physical processes shaping planetary nebulae, confirming Herschel’s eighteenth-century discovery as one of enduring astronomical importance.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 1501 04h 07m 0s +60° 55’ Planetary nebula 11.5 References:

- Sabbadin, F., Benetti, S., Cappellaro, E., Ragazzoni, R., Turatto, M. & Costa, E., 2000. The True Shape and Structure of Planetary Nebulae: NGC 1501. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 355, pp.688–696.

- Bond, H. E., Ciardullo, R. & Meakes, M. G., 1996. Pulsations of the Hydrogen-Deficient Central Star of the Planetary Nebula NGC 1501. Astronomical Journal, 112(6), pp.2699–2707.

- Ercolano, B., Wesson, R., Zhang, Y., Barlow, M. J., De Marco, O., Rauch, T. & Liu, X.-W., 2004. The 3D Photoionisation Structure of the Planetary Nebula NGC 1501 and its Hydrogen-Deficient Central Star. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 354(2), pp.558–576.

-

NGC 381 in Cassiopeia

October 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

In October, the nights lengthen and observing becomes easier. The temperatures are not yet at their winter lows, yet the astronomical darkness reaches 13 hours by the end of the month. The brilliant winter constellations (at least I’m told that they’re brilliant; from my back garden they’re barely visible against the claggy, light-polluted sky) begin to make their presence known in the east as the month progresses.

Our object this month is a little-observed cluster in Cassiopeia. It sits very close to the galactic equator and culminates at midnight around the middle of October, when it reaches an altitude of 82° from mid-Britain.

An image of open cluster NGC 381 in Cassiopeia taken by Patrick Maloney with his ZWO Seestar S50. It was discovered in 1783 by Caroline Herschel and included in her brother William’s class VIII (coarsely scattered clusters of stars) after he observed it on 3 November 1787. He described it as

A forming cluster of pretty compressed stars. CH discovery 1783.

Herschel did not use the word ‘forming’ in a modern astrophysical sense. If so, the phrase would mean that the individual stars were still forming, and the object would probably still be swathed in the nebulosity that does actually give birth to clusters. Instead, he used it in the sense that he thought the stars may be beginning to gather together to form a cluster. The use of the word suggests that Herschel theorised that clusters formed by stars clumping together. It is best interpreted as meaning ‘loose’ or ‘poorly condensed’.

The cluster made its way into the NGC as number 381, its NGC description being a somewhat terse

Cluster, pretty compressed

.The sources are surprisingly consistent in the vital statistics of NGC 381. The greatest variation is with the Trumpler type, which can be summarised as III 1(or 2) m(or p). This means that there is agreement that there is no central condensation, but the cluster does appear detached from its background; it has a moderate range of brightnesses (or the stars are all of similar magnitude), and it has a medium richness (or it’s poor). All sources agree that the cluster contains 50 stars, so it can’t be poor by definition. It always amazes me that sources can quote a number of member stars and then give a Trumpler classification that blatantly ignores the number.

Deep images of the cluster, reaching around 20th magnitude, have revealed several hundred probable members.

One agreed vital statistic that I can’t understand at all is the magnitude of the brightest star in the cluster. It is usually given as magnitude 10.0 (or 10.9 in one instance). The Night Sky Observer's Guide adds that the brightest star is located in the chain of stars that heads north. My investigations suggest that none of the stars in that chain exceed magnitude 11, and most are around magnitude 12. The nearest tenth-magnitude star is the eclipsing binary OX Cas, which is given the optimistically exact magnitude of 9.996.

No star in this cluster reaches magnitude 10. The brightest stars are eleventh magnitude. Ho hum.

NGC 381 lies at a distance of around 2900—3300 light-years and is an intermediate-age cluster, its age usually being quoted within the range of 200—300 million years. At this age, it will be partially evaporated. Far, then, from a ‘forming’ cluster, it is a disintegrating cluster.

The cluster is fairly easy to find, being 1.6° to the north-east of γ Cas (the middle star in the ‘wonky wubbledoo’ of Cassiopeia).

Visually, it is immediately recognisable as a cluster. With an overall magnitude of 9.3, it is visible even in quite small telescopes. It is well detached from its background and stands out well. I observed it with my 12” Newtonian in October 2015. On that night, I described it as

A small, reasonably compressed and moderately rich cluster of very faint stars. About 30 stars counted across about 7 or 8'. A chain of brighter stars (maybe not members) leads away to the north.

Most visual observers remark on this chain of stars. To my eyes (either when looking at the object or at an image of the object), it does not look to be physically associated with the cluster itself. A quick look at proper motion data suggests the same. In fact, several of the brighter stars within the cluster seem to have a fairly random scatter of proper motions.

When observing it, then, bear in mind that the cluster is beginning to break apart, and probably only the compressed small stars are actually cluster members.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 381 01h 08m 20s +61° 35’ Open cluster 9.3 -

NGC 40 in Cepheus

September 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

Our object for September is the planetary nebula NGC 40, in Cepheus. It presents something of a contrast between the descriptions given by early observers and those of the present.

It was first observed (quelle surprise) by William Herschel on the night of 25 November 1788. His description runs

A star of ninth magnitude with a very faint, milky nebulosity. The star is either double or not round. Less than 1’ diameter.

He included it in his fourth class (‘planetary nebulae’) as 58 H.IV. It passed through various catalogues; in John Herschel’s Slough Observations of 1833 it is number 8, in John Herschel’s later General Catalogue it was number 20 and then in the New General Catalogue it became number 40. By the time it reached the NGC, the description had become

Faint, very small, round, very suddenly much brighter in the middle. Star, mag 12 south preceding.

William Herschel’s description and that of the NGC are separated by 100 years during which time the object remained basically small and very faint. More recent observations tend to differ, as I will show later.

An image of planetary nebula NGC 40 in Cepheus provided by WIYN/NOIRLab/NSF. Physically, NGC 40 lies at a distance of about 1618 parsecs (5277 light-years)1, which gives it a true diameter of about one light-year. All pretty normal.

The nebula presents a barrel-shaped appearance, with the long axis aligned to the north-northeast. It has two bipolar lobes, probably caused by two separate mass ejections from the central star. The age of the nebula has been calculated as about 5,800 ± 600 years.2

The central star shines at magnitude 11.6, though this is slightly variable. The star bears the variable star designation of V400 Cep. It is a Wolf-Rayet star, rich in carbon and deficient in hydrogen.

Deep observations of the nebula with large telescopes reveal concentric haloes surrounding the central nebula while a much fainter outer spread of nebulosity extends up to four minutes in diameter, corresponding with a true diameter of about six light-years3.

NGC 40 has been intensively studied and presents a good model for the future of Sun-like stars. One day, our star will produce a planetary nebula like NGC 40, will evolve into a Wolf-Rayet star, then eventually the nebula will dissipate and the Sun will shrink to become a white dwarf and then very slowly cool down.

On now to modern observations. Whilst the early observers called NGC 40 small and faint, that does not appear to be the prevailing opinion of more recent observers. Maybe it’s a matter of expectation. If, like me, you’re used to hunting down virtually stellar, 14th magnitude planetaries, this object comes as a real contrast.

The magnitude quoted for this object varies considerably. Some sources insist on 12.4 whilst others prefer 10.6 or 10.7. It tends to be the older sources that give the lower value. I’m not suggesting that this object has brightened, just that some planetary nebula magnitudes have been reappraised. It is my experience that NGC 40 is much brighter than 12th magnitude.

The late Steve Coe, in his published observations, describes NGC 40 as

bright and large

.In The Night Sky Observer’s Guide Volume 1, NGC 40 is described as viewed through telescopes of the 12”–14” class and telescopes of the 16”–18” class.

The 12”–14” observation describes the nebula as bright and ‘a spectacular object’.

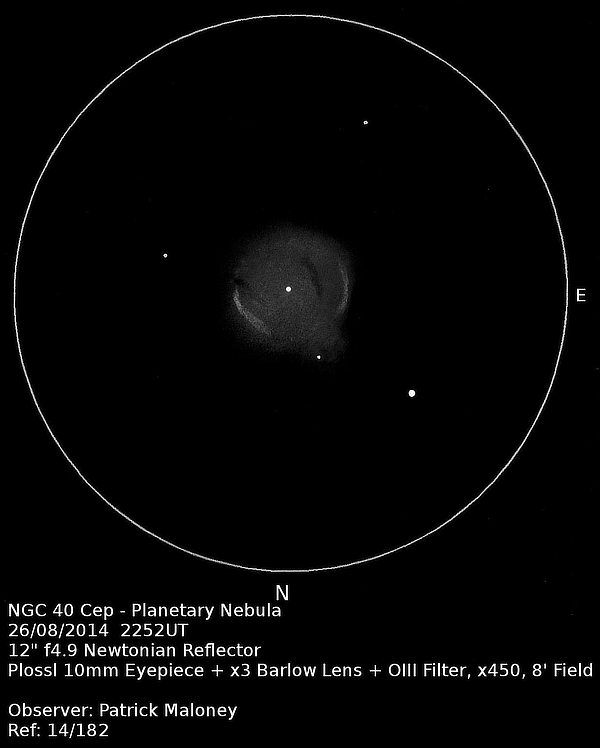

I would concur. My own observation (shown below) is accompanied by a very enthusiastic description:

Very, very bright. Very large and immediately obvious even at x83. Pretty circular, but not evenly bright. Brighter arcs were seen on the southeast and northwest edges. Some darker patches were also noted. A small extension away from the disc was noted to the northeast, associated with a small star. The OIII filter adds nothing, merely removing the brilliant central star from view. A lovely object giving a different view with every power.

A sketch of planetary nebula NGC 40 in Cepheus by Patrick Maloney through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x450 magnification with an O-III filter. NGC 40 is well worth a look this September. It presents a wealth of detail under sufficient power. Don’t be afraid of using high power on planetary nebulae. The old adage that wide-field is best for deep-sky is an old wives’ tale and does not apply to most deep-sky objects. Greater magnification gives greater contrast and is a must for planetary nebula observing.

Whilst you are gazing at it, it is interesting to bear in mind that you are looking at the probable future of our own Sun.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 40 0h 13m 01s +72° 31’ Planetary nebula 10.7 References:

- Frew, D. J., Parker, Q. A., & Bojičić, I. S. (2016) ‘The Hα surface brightness–radius relation’, MNRAS, 455, pp. 1459–1488.

- Meaburn, J., López, J. A., Bryce, M., & Redman, M. P. (1996) ‘Kinematics and evolution of planetary nebulae with Wolf–Rayet nuclei’, MNRAS, 282, pp. 1313–1324.

- Chu, Y.-H., Jacoby, G. H., & Arendt, R. (1987) ‘Planetary nebula halos and progenitor mass loss’, ApJ, 322, pp. 899–904.

-

NGC 6939 in Cepheus

August 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

August brings with it the welcome return of dark skies, and a plethora of clusters and nebulae become available for observation. This month, we’re going to be looking straight up. In mid-Britain, this open cluster transits at midnight on the 17th August, reaching an altitude of 83°.

It is NGC 6939 and it lies in Cepheus, very close to its border with Cygnus. Discovered (predictably) by William Herschel on the night of 9 September 1798, it became the final entry in his sixth class –

Very compressed and rich clusters of stars

, as 42 H.VI. On that night, he described it asA beautiful compressed cluster of small stars, extremely rich, of an irregular form. The preceding part of it is round, and branching out on the following side, both towards the north and towards the south, 8 or 9’ in diameter

.The description may seem a little obscure, but comparing it with my observation, I think I know what he meant. When the object entered the NGC in 1888, the description became

Cluster, pretty large, extremely rich, pretty compressed towards the middle, stars magnitudes 11—16

. This is a pretty good description of the object’s appearance in a moderate telescope.NGC 6939 is located about 4000 light-years (1200 parsecs) away, close to the edge of the galactic disc. The stars within open clusters are loosely bound gravitationally, but these gravitational bonds are disrupted and eventually broken by tidal forces within the Galaxy. Clusters therefore ‘dissolve’ over time, their constituent members being pulled away from the cluster to lead more solitary lives. It is quite likely, for example, that the Sun was once a member of a now-dissolved open cluster. NGC 6939, being well away from the strongest tidal forces, has so far escaped this fate and has survived to an unusually old age (see also the article on NGC 188 for May, 2025). Estimates of the cluster’s age vary between 1 billion and 1.6 billion years, depending on the method used1,2, compared with about 6.2 billion years for NGC 188.

In addition to its age, NGC 6939’s chemical composition, specifically its metallicity, has also been studied extensively. The [Fe/H] values of its component stars are lower than those found in stars in the solar neighbourhood. This has been used as evidence to support the theory that the Milky Way has a metallicity gradient, in which the metallicity of stars decreases with distance from the core3.

NGC 6939 is thus an important object in the field of astrophysics, and has served as an experimental test-bed for several theories.

It forms a triangle with the stars η and θ Cephei, being 2° southwest of η and 2.3° south of θ. On a good night and with sufficient magnification, it makes a very fine sight. I observed it with my 12” (300mm) Newtonian in July 2016 and found it to be small, rich and compressed. I described the brightest stars to be of about 12th magnitude, forming two straight lines at right angles to each other. These, I think, may be the branches described by Herschel. The cluster is well-detached from the background stars and stands out immediately the field is found.

More recently, I took a picture of the cluster, a short exposure that gives a reasonably good impression of how the object appears through a moderate telescope.

An image of open cluster NGC 6939 in Cepheus taken by Patrick Maloney with his ZWO Seestar S50. Drifting away from nebulae and clusters for a moment, it would be remiss of me not to mention the very fine galaxy, NGC 6946, which lies 39’ to the southeast of NGC 6939. This is a large, open-armed, face-on spiral galaxy. Its magnitude is given as 8.8, but this is misleading. It has a low surface brightness and can be quite tricky to see. I found when I observed it that there was something quite ‘planetary nebulary’ about it. I was pleased, therefore, when I found out that William Herschel (who discovered it, of course) had placed in his fourth class – planetary nebulae.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 6939 20h 31m 31s +60° 40’ Open cluster 7.8 References:

- Bragaglia, A., Tosi, M., Marconi, G., & Carretta, E. (2001). NGC 6939: An old open cluster in the outskirts of the Galactic disc. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 371, 527–535.

- Rosvick, J. M., & Balam, D. D. (2002). A CCD study of NGC 6939. The Astronomical Journal, 124(4), 2093.

- Dias, W. S., Alessi, B. S., Moitinho, A., & Lépine, J. R. D. (2002). New catalogue of optically visible open clusters and candidates. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 389, 871–873.

-

NGC 6778 in Aquila

July 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

It can be difficult to believe, but by the end of July, mid-Britain has regained a small measure of Astronomical darkness. The nights are still short and bright, though, so every opportunity to observe should be seized.

Moving to centre-stage this month is the great northern sweep of the Milky Way through Cassiopeia, Cygnus and Aquila, bringing with it many open clusters and planetary nebulae.

Our object this month has the distinction of having two discoverers and consequently two entries in the NGC. John Herschel made the first known observation of this planetary nebula in 1825, his description being

extremely small, stellar

. This object entered the New General Catalogue in 1888 as NGC 6785.In 1863, the object was observed by Albert Marth, discoverer of around 600 NGC objects. His position was slightly different from that of John Herschel, and became NGC 6778. Marth’s description was

small, elongated, ill-defined disc

. The positions listed in the original NGC are slightly different, but it is now recognised that these two objects are identical.I shall refer to the object as NGC 6778, as this is how it is usually referenced. The reason why the later discovery should be preferred is simply because it has the lower NGC number, in turn because the original measurements gave this entry the westernmost Right Ascension.

Nordic Optical Telescope composite color picture of NGC 6778 in Aquila taken from La Palma, Canarias. Taken from the paper NGC 6778: a disrupted planetary nebula around a binary central star, M. A. Guerrero, L. F. Miranda, A&A 539 A47 (2012), DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201117923 Although small and not very bright (listings vary, but all are between magnitude 12.1 and 12.4), this planetary nebula has been the subject of much study because of its complex morphology and unusual chemical makeup.

The defining feature of NGC 6778 is its binary central star, which has an orbital period of just 3.68 hours. Such a short period indicates that the system underwent a common-envelope phase, during which material from the secondary star spiralled into the envelope of the primary, ejecting the outer layers and creating the nebula's present form1. This interaction is believed to have generated the nebula’s bipolar lobes, bright knots, and high-speed jets.

Spectroscopic studies show collimated outflows moving at speeds of up to 100 km/s 2. These jets disrupt the nebula’s equatorial ring, leading to a chaotic appearance filled with bright knots, filaments, and complex internal structures. Such features are often associated with close binary interactions, highlighting the role of binarity in shaping planetary nebulae3.

One of the most intriguing aspects of NGC 6778 is its abundance discrepancy factor (ADF). This factor compares abundances calculated from spectral recombination lines to those from collisionally excited lines. Typically, planetary nebulae show modest ADFs, but NGC 6778 exhibits an ADF averaging about ten times the normal values and peaking at nearly twenty times near its centre. Such extreme values imply chemically distinct regions within the nebula, potentially representing material ejected during a late thermal pulse or binary interaction event.

From the perspective of the visual observer, NGC 6778 is not particularly spectacular, but not difficult to see. An 8” or 10” (200–250mm) scope will show a very small, rounded disc. Under most conditions, an OIII filter (or failing that, a nebula filter) will be needed to distinguish it from a star.

A 12” or 14” (300–350mm) scope will reveal something of its elongated shape, and possibly even a glimpse of the central star. The magnitude of the central star is given various values in the sources (14.8, 16.9). Some observers report having glimpsed the star with 14” scopes, suggesting the true value is towards the brighter of the given values.

A sketch of planetary nebula NGC 6778 in Aquila by Patrick Maloney through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x450 magnification with an O-III filter. I observed the planetary with my 12” (300mm) Newtonian reflector in July 2014 under different magnifications. At x83, it was seen as a small disc. It was pretty faint but visible to direct vision with no OIII filter. x375 reveals a suggestion of elongation. It was seen to be brighter in the middle, but there was no real sign of a central star. There is some outer, fainter nebulosity. The OIII filter increases the object’s brightness but adds no details.

Pushing my scope, I increased the magnification to x450, the inner core of the nebula now being distinctly brighter than the outer envelope. At this magnification, the OIII filter made little difference and added nothing to the view.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 6778 aka NGC 6785 19h 18m 25s -01° 35’ Planetary nebula 12.4 References:

- Miszalski, B., Jones, D., Rodríguez-Gil, P., et al. (2011) 'Binary central stars of planetary nebulae discovered through photometric variability', MNRAS, 413(2), pp. 1264–1278.

- Corradi, R.L.M., Sabin, L., Miszalski, B., et al. (2011) 'Fast collimated outflows in planetary nebulae with close binary central stars', MNRAS, 410(2), pp. 1349–1358.

- Jones, D. and Boffin, H.M.J. (2017) 'Binary stars as the key to understanding planetary nebulae', Nature Astronomy, 1, p. 117.

-

NGC 6369 in Ophiuchus

June 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

June, in addition to providing us with the brightest nights of the year, is also the month when clusters and nebulae become more easily available. The rich star fields of the Milky Way begin to swing back into prominence, and with them a profusion of Galactic treats.

Amongst the constellations most blessed with these objects is Ophiuchus, rather low in British skies, which means it tends to be overlooked somewhat by visual observers, especially those in light-polluted areas (which is just about everybody these days).

Nevertheless, Ophiuchus is well worth a long study, and this month we’re going to look at one of its delights, the planetary nebula NGC 6369.

An image of planetary nebula NGC 6369 in Ophiuchus provided by Sid Leach. As with most of the objects presented here, this one was discovered by William Herschel, who first saw it on 21 May 1784. On that night, he described it as

Pretty bright, round, pretty well-defined planetary disc, 30 or 40” diameter.

Recent research into this planetary nebula seems to be largely absent. Distance estimates range from 2000 to 4000 light-years (or even 5000 in some cases). This indicates a true diameter of the object as anywhere between 0.3 and 0.6 light-years (or even 0.7 light-years!). These are fairly typical values for planetary nebulae, if not very precise.

The central star, which shines at magnitude 15.6, is a challenging object for visual observers. Its spectrum is classed as [WO3]. The straight brackets indicate that the spectrum resembles that of a WO3 star, but is not the spectrum of a WO3 star. A WO3 star is an oxygen-rich Wolf-Rayet star (supermassive and superluminous). The central stars of planetary nebulae are white dwarfs, typically with lower masses than the Sun, but considerably hotter and brighter.

The central star appears to be a binary and was once suspected of being a pulsating variable. It has the variable-star designation V2310 Ophiuchi. Examination by the Kepler Space Telescope revealed no variations1.

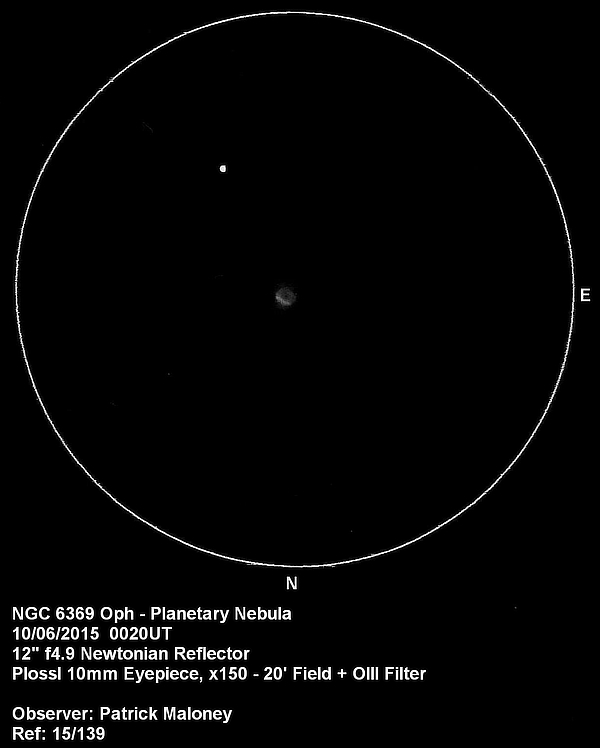

A sketch of NGC 6369 in Ophiuchus by Patrick Maloney through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x150 magnification. Visually speaking, Herschel’s description still holds true. My observation was made with a 12” (300mm) Newtonian telescope from light-polluted skies. I found that I could not see the planetary at all without the use of an OIII filter. These filters are invaluable and are an essential piece of kit for any planetary nebula hunter. If you live further south and/or have less light pollution than me to your south, you may well be able to see it without a filter. It is fairly bright at magnitude 11.4.

Once the OIII filter was in place, the object was very clear to see. The nebula presents itself as small, quite bright and circular. The surface brightness is uneven, being noticeably brighter along the north to northwest edge. Other observers have noted this, and white light images bear this out. Averted vision gives a suggestion of annularity, and there was even an occasional hint of the central star (which I admit came as something of a surprise).

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 6369 17h 29m 20s -23° 45’ Planetary nebula 11.4 References:

- Jacoby, George H.; Hillwig, Todd C.; Jones, David; Martin, Kayla; De Marco, Orsola; Kronberger, Matthias; Hurowitz, Jonathan L.; Crocker, Alison F.; Dey, Josh (2021). ‘Binary central stars of planetary nebulae identified with Kepler/K2’. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 506

-

NGC 188 in Cepheus

May 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

May is another month when I find myself struggling to find objects to write about. According to my own rules, the object in question should culminate at midnight some time in the current month, and should be visible from central Britain. Unfortunately, I’ve more or less run out of suitable subjects for May.

This month, then, I’m going to bend my own rules (possibly to breaking point, I’ll let you decide). I’m going to ask you to swing your telescopes away from the south and peer north for once.

Right up there, just 5° from the pole, is a very interesting open cluster. If you look at it during May, you will find it approaching its lower culmination, when it is actually at its lowest in the sky, but it will still be around 50° above the northern horizon. It is located 4° from Polaris, just east of the line that joins the pole star to γ Cephei.

It was missed by William Herschel and had to await discovery by his son, John. It entered his catalogue of observations, published in 1834, as no. 34. He described it as

Cluster, very large, pretty rich 150 – 200 stars of magnitudes 10 – 18; more than fills the field

.The entry was carried forward into John’s General Catalogue (GC) as no. 92 and subsequently into the New General Catalogue (NGC) of 1888 as no. 188. The NGC description is the same as that originally penned by John Herschel, bar the comment about it more than filling his field.

An image of open cluster NGC 188 in Cepheus by Patrick Maloney. NGC 188 is a large, rich cluster. It spans around 13’ in diameter. For once, I feel quite justified in using the term ‘diameter’ for an open cluster, because NGC 188 is pretty round. The overall magnitude is usually given as 8.1, but the brightest member stars of the cluster are of magnitude 12, not 10 as stated by John Herschel. There are stars in the field of 10th magnitude, but they are not members of the cluster.

NGC 188 was often touted as the ‘oldest open cluster in the Milky Way’. It is now not believed to be so, not because it isn’t very old, but because other, older clusters have now been observed. It is, however, probably the oldest open cluster that is readily available to users of modest telescopes.

Søren Meibom et al conducted an investigation1 into NGC 188 in 2008. They focused on a variable star known as V12, a member of the cluster. V12 is a spectroscopic eclipsing binary with a period of 2.9 days.

The mass and radius of each star in a spectroscopic binary can be determined by observation of the spectrum and light curve. A less direct method was used to determine the age of the stars and thus that of the cluster as a whole.

They concluded that the cluster was 6.2 billion years old (± 0.2 billion years) and that it lay at a distance of 1770 ± 75 parsecs, or 5770 ± 244 light-years.

The distance places it well north of the plane of the Milky Way and explains why it has survived to such a great age. It is well away from the gravitational influences that pull open clusters apart within the galactic plane. It is further from the galactic centre than we are.

Visual observers may find NGC 188 a little underwhelming at first sight, but it rewards careful study. I was fortunate to be in a very dark-sky site when I observed it in 2015. I noted that it was a large, fairly untidy cluster of scattered stars defined by two parallel lines of 11th and 12th-magnitude stars. It appeared fairly well detached and was rich. I estimated its diameter as 15’. Careful observation reveals seemingly hundreds of faint twinkles in the background.

The Trumpler type given in various catalogues for NGC 188 is usually I2r, indicating a well-detached cluster with strong central condensation, a moderate range of magnitudes and which contains over 100 stars. Archinal & Hynes quote a membership of 550 stars (including stars up to 10th magnitude) whereas the Deep Sky Field Guide to Uranometria suggests a more modest 120.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 188 00h 47m 20s +85° 15’ Open cluster 8.1 References:

- Søren Meibom et al 2009 Astronomical Journal 137 5086

-

NGC 5466 in Boötes

April 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

I hope you are all enjoying the spring galaxy season. Following on from the galaxies by midnight in the middle of April, we have a small grouping of four globular clusters coming into fine view. Two were observed by Charles Messier and included in his famous catalogue; M3 – see this column for April 2021 – and M53, and two fainter clusters which were discovered by William Herschel; NGC 5053 and NGC 5466.

This month we’ll be looking at NGC 5466. Discovered on the night of 17 May 1783, Herschel placed it in his category VI (very compressed and rich clusters of stars) as entry no. 9. In his catalogue, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1786, he describes it as

A cluster of extremely small and compressed stars, 6 or 7’ diameter. Many of the stars visible, the rest so small as to appear nebulous.

This is still a very good description, and gives a good idea of what this object looks like through a modest telescope on a good night.NGC 5466 lies in the west of Boötes, close to the border with Canes Venatici and 5° west of M3. The nearest Flamsteed-designated star is the 6.2-magnitude 11 Boo. The cluster lies at a distance of about 52,000 light-years. It shows signs of gravitational disruption, particularly in that it has a very long ‘tail’ of stars streaming behind it. The tail, or ‘tidal stream’ is very difficult to detect, but may be as much as 60° long. This is seen as evidence of tidal interactions between the globular cluster and the Milky Way. Some researchers have suggested that there have also been one or more interactions with the Large Magellanic Cloud1.

An image of globular cluster NGC 5466 in Boötes courtesy of Adam Block. Although the catalogue magnitude of this object is given as 9.2, be aware that this is very misleading. NGC 5466 has very poor concentration, with no visually noticeable brightening towards the centre. Its concentration class is XII, the lowest, indicating a very loosely compressed object.

I first searched for NGC 5466 on 24 March 2014, whilst the object was the Webb Deep-Sky Society’s Object of the Season2. I classed my first attempt from my light-polluted home site as a ‘not seen’, though my notes from that night say

There is a very small scattering of very faint stars where this object lies. This may be all I can see of it.

On further reflection, I realised that I should not expect to see a ‘globular cluster’ as such – a ball of stars with a distinctly brighter centre and an unresolved haze of background stars. The low concentration suggested that what I would most likely see (from under light-polluted skies at any rate) would be just what I did see – a scatter of the brightest individual member stars of the cluster and nothing else.

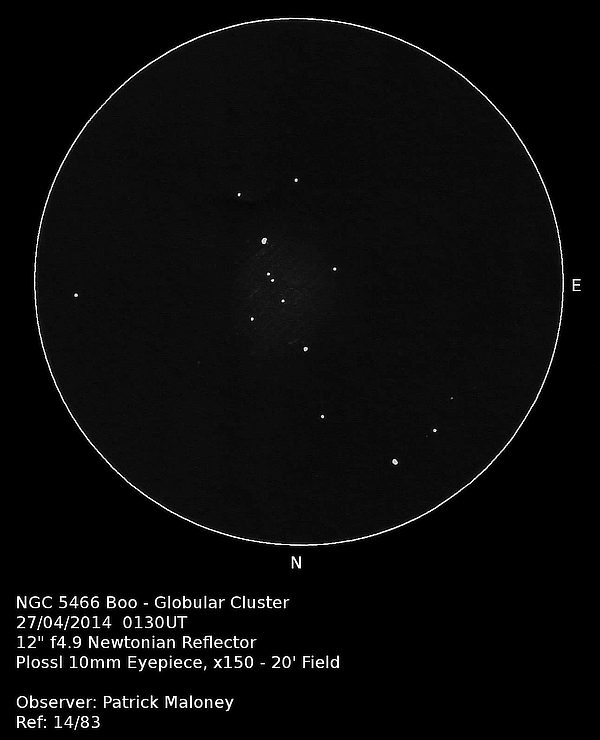

I returned to the object on the somewhat better night of 27 April 2014. I had more success this time. I detected a large but very dim patch – a very low-level glow. I only recognised it because of the faint scatter of stars across it. All the stars were very faint and difficult to place with any precision as they twinkled in and out of visibility. I made a sketch, reproduced here.

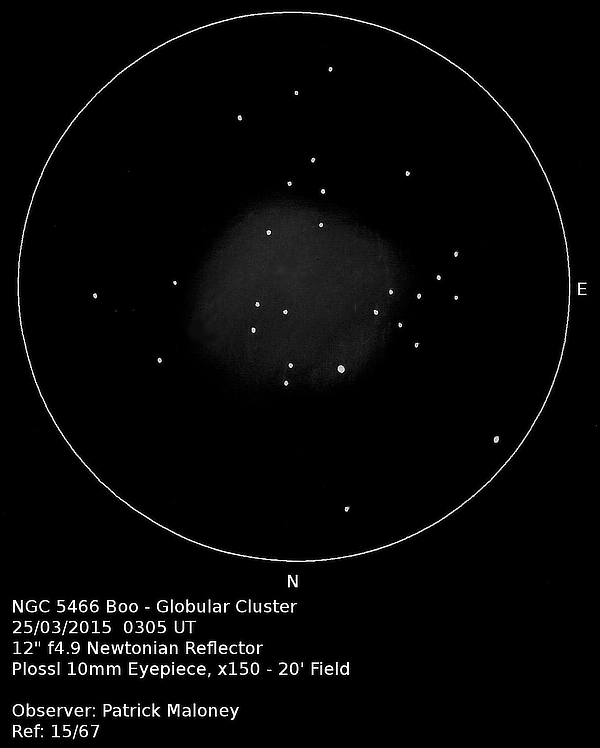

A sketch of NGC 5466 in Boötes by Patrick Maloney in 2014 through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x150 magnification. Nearly a year later, on 25 March 2015, I was at my regular dark-sky site in the Lake District. I described the night as cold and fairly crisp. The naked eye limiting magnitude was 5.8 and the object glass of the finder scope iced over. I couldn’t resist the opportunity to look at NGC 5466 under vastly superior conditions to those I could ever get at home.

It was quite a revelation. I had an amazing view. I could see a huge, pale, circular patch with dozens of stars splashed across it. Only 28 of those stars were certain enough to plot, with many others blinking in and out of sight, tantalisingly on the edge of visibility.

A sketch of NGC 5466 in Boötes by Patrick Maloney in 2015 through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x150 magnification. The final chapter (so far) of my personal history with NGC 5466 occurred on 14 March 2025. As the sky conditions at my home are now so poor, I cannot observe visually any more. For a recent birthday, I was bought a SeeStar S50, a marvellous little machine which means although I am no imager (I have no idea at all what a ‘luminance frame’ is, for example) I can at least now do something on a clear night. On this particular night, I returned to NGC 5466. The result is reproduced below, a 30-minute exposure that gives a pretty good impression of what this object looks like visually.

An image of NGC 5466 in Boötes by Patrick Maloney taken in 2025 with his SeeStar S50. With many thanks to my family for the SeeStar.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 5466 14h 05m 28s +28° 32’ Globular cluster 9.2 References:

- See, for example, Yong Yang et al., ‘Revisit NGC 5466 tidal stream with Gaia, SDSS/SEGUE, and LAMOST’, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 513, Issue 1, June 2022, Pages 853–863.

- The Deep-Sky Observer, Issues 163, 165 and 166.

-

NGC 2419 in Lynx

January 2025 - Nebula and Cluster of the Month

January brings with it the hope of a better year, of new beginnings. Let’s all hope for clearer skies and for an awakening amongst those who can make a difference, of the damage done by light pollution. I wish you all a happy and peaceful new year.

On the night of 31 December 1788, William Herschel was examining the sky in the region where the constellations of Gemini, Auriga and Lynx meet. He was engaged in his ‘sweeping’, whereby he swept the telescope across an area of sky to find new ‘nebulae’ and clusters of stars. On this night, he came across a bright nebulous object in the southern regions of Lynx and fixing its position by its difference in Right Ascension and Declination from the 4.9 magnitude star 63 Aurigae, some 5.2° away, he described it as

Considerably bright, round, very gradually much brighter in the middle. About 3’ diameter.

He considered the object bright enough to fit his first class of objects, ‘bright nebulae’ and assigned it the number 218 within that class. It was, in fact, one of the 39 globular clusters discovered by Herschel during his sweeps. At the time, he can hardly have been aware of the significance of this object.

An image of Globular cluster NGC 2419 courtesy of Adam Block. Herschel did not resolve the object into stars and made no indication that he believed it to be anything other than a nebula. In the nineteenth century, the third Earl of Rosse, using his gigantic 72” reflector at Parsonstown in County Offaly, first resolved the object into stars and declared that he believed it to be a globular cluster.

In 1888, a century after its discovery, 218 H.I entered the New General Catalogue as NGC 2419. There was an oddity about NGC 2419. As a globular cluster, it looked perfectly normal, but its positioning was strange. To an observer on Earth, it is the most remotely placed globular cluster, being well away from the main clustering of these objects in Sagittarius and Scorpius – i.e. towards the galactic centre. NGC 2419 lies about as far as it’s possible to get from the direction of the galactic centre.

In 1922, the first photographs of NGC 2419 confirmed Rosse’s discovery; the object was indeed a globular cluster.

In the 1920s, Harlow Shapley, using the period-luminosity relationship of its variable stars, calculated the globular’s distance to be 99,000 light-years. The period-luminosity relationship has since been refined, with the recognition of the difference between delta-Cephei variables and RR Lyrae variables, leading to a revised distance of around 272,000 light-years from Earth, or 300,000 light-years from the galactic centre.

This colossal distance (three times the galactic diameter) led to the belief that NGC 2419 was not gravitationally bound to the Milky Way and must therefore be an ‘intergalactic wanderer’, and so its popular name was coined. Even today, some sources still insist that this is so, or that the velocity of the globular cluster is greater than the escape velocity of the Milky Way.

Romantic as it sounds, it’s not true. The popular name is a misnomer. NGC 2419 is actually part of the Milky Way system, taking a mind-boggling three billion years to make a single orbit of the Milky Way.

It has been noted that if an observer in M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, were to observe our Galaxy, NGC 2419 would be the brightest Milky Way globular visible, being far removed from the dust and gas which would obscure many of the other globular clusters.

Despite its great distance, NGC 2419 is not the furthest-flung of the Galaxy’s globulars. There are three even more distant; Palomar 3, Palomar 4 and Arp-Madore 1 and these, too, are still gravitationally bound to the Milky Way. However, at magnitudes 13.9, 14.2 and 15.8 respectively, NGC 2419 is still the most far-flung outpost of the Galaxy that we’re likely to see visually.

There is another oddity about NGC 2419. Most globular clusters consist of stars all of which are approximately the same age. They form a single population, in the terminology of astronomers. It’s believed that globular clusters form in a single event, and the absence of spare gas and dust prevents the formation of further stars once the initial formation is complete.

NGC 2419, however, has been discovered to have two very distinct populations. One population is considerably richer in helium than the other. There is currently no satisfactory explanation for this anomaly.

NGC 2419 is physically a large, bright globular cluster. If it were the same distance as M13 in Hercules, it would be half as big again as that globular and a full magnitude brighter. As it is, at its remote distance, it shines at magnitude 10.3, still a relatively easy target for modest telescopes. Fortunately for us, it is compressed, a type II in the 12-type classification of globular cluster concentration. This means that the brightness of the constituent stars is contained within a small diameter, rather than loosely spread out.

A sketch of NGC 2419 in Lynx by Patrick Maloney through his 12-inch newtonian telescope at x81 magnification. It lies about 7.5° north of Castor, α Geminorum, in a fairly blank region of sky. It is about 4.1’ in diameter, and on low finding powers can look like a star, one of a row of three, the other two of which are around seventh magnitude. There are several fainter stars scattered around, but none of them are members of the cluster. The faintest stars on my drawing are around magnitude 13.5. The brightest member star of the cluster is magnitude 17.3, so not much hope of visual resolution unless you have an unfeasibly huge telescope (say a 72”).

Nevertheless, it is comfortably bright enough to be easily visible, and the brightness difference between the outer periphery and the inner core is quite marked. Despite not being able to resolve the globular, I did note that it appeared somewhat mottled and the core appeared bulbous.

I’ll be taking a break for the next couple of months. The criteria that I use to select objects for each month mean that there is nothing suitable left for February and March. I’ll be back in April. Until then, I hope your skies are clear and dark.

Object RA Dec Type Magnitude NGC 2419 07h 38m 08s +38° 52’ 54” Globular cluster 10.3