Double Star of the Month in Boötes

-

May 2024 - Double Star of the Month

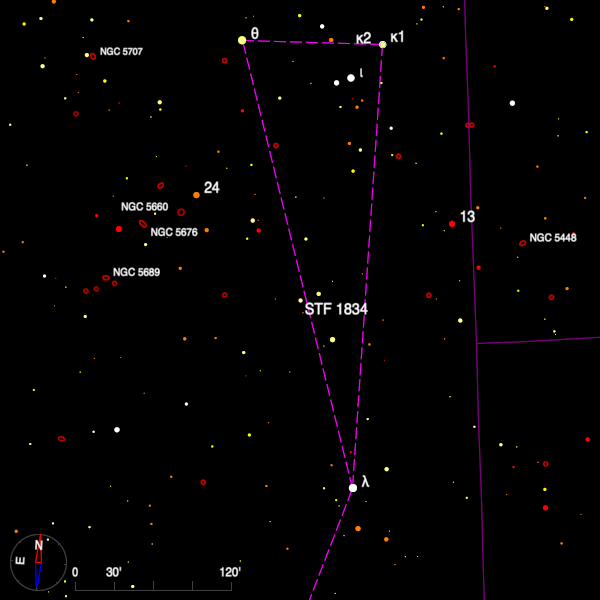

STF 1834 (14 20 17,6 +48 30 25.1) sits in the north of Boötes, about half way between theta and lambda Boo and 2.5 degrees north north-east of the latter.

A finder chart for the double star STF 1834 in Boötes created with Cartes du Ciel. It is a well-known binary and the Washington Double Star catalog (WDS) notes than 250 direct measurements have been since discovery by Struve at Pulkova. From about 1830 to 1900 the two stars, magnitudes 8.1 and 8.3, closed steadily from 1".7 but then in just a few years the companion swung around its partner at which point it was out of range of even the large refractors of the time and began heading out towards the discovery position.

The period of the pair is 413 years and at the present time the position angle and separation are 204 degrees and 1".7. The relative faintness of the stars would suggest that an aperture of 15-cm would be better to view them.

About 1 degree south-east is STF 1843, a pair of stars of magnitude 7.7 and 9.2 currently at 186 degrees and 19".8. The stars lie at a similar distance and have common proper motion.

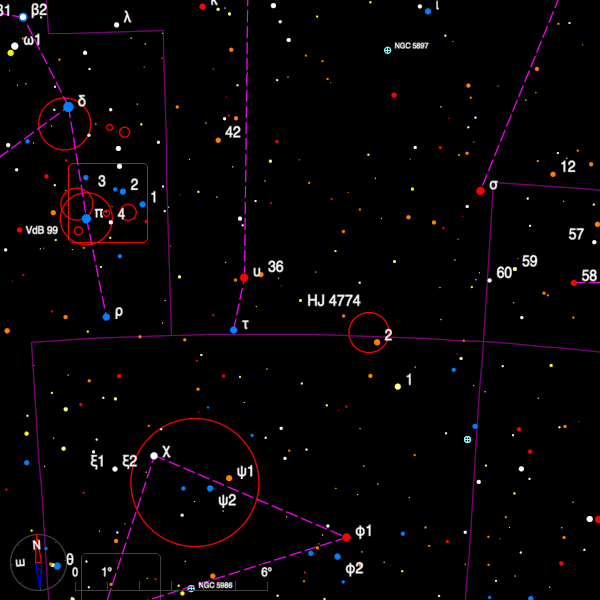

Near the border of Libra with Lupus, HJ 4774 (15 28 58.69 -28 52 00.5) was discovered by John Herschel from Feldhausen during his stay at the Cape of Good Hope. The brightest star is magnitude 7.0 and has a 9.6 magnitude companion almost 10 arc-seconds distance in PA 11 degrees.

A finder chart for the double star HJ 4774 in Libra created with Cartes du Ciel. In 1889 the eagle-eyed S. W. Burnham found that the primary star was double again with a 7.7 magnitude star at a distance of 0".7. Since then the separation of the close pair has closed to 0".1. A recent orbit by Dr. Andrei Tokovinin indicates that the orbit is only 0.6 degrees from being edge-on and in 2027 when periastron occurs the two stars will be only 8 milliarcseconds apart.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

May 2023 - Double Star of the Month

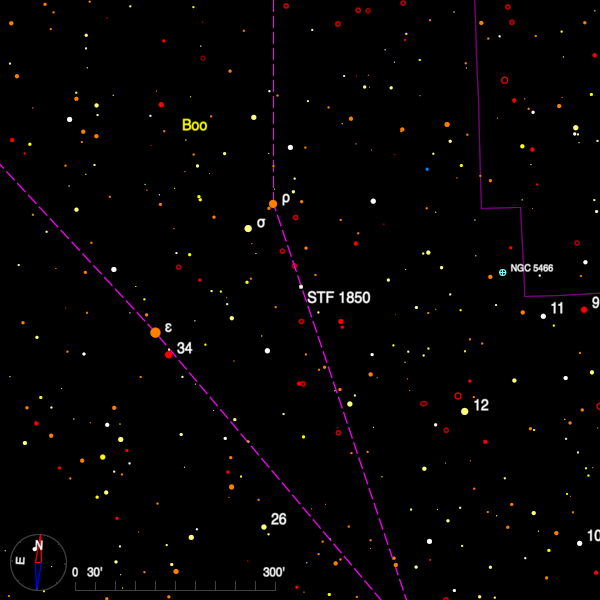

STF 1850 (14 28 33.239 +28 17 25.9) is a wide and fairly bright pair which can be found 3.5 degrees WNW of the spectacular pair epsilon Boötis also known as Pulcherrima - 'most beautiful' (see the column for May 2020).

A finder chart for the double star STF 1850 in Boötes created with Cartes du Ciel. The stars have changed little in relative position since they were catalogued by F. G. W. Struve and they are currently separated by 25" in PA 263 degrees. Although both are given spectral class A1V by the Washington Double Star catalog (WDS), the stars are magnitudes 7.1 and 7.6. They are rather distant, and Gaia DR3 gives the mean distance of the two as 873 light-years with an uncertainty of 1% in each case.

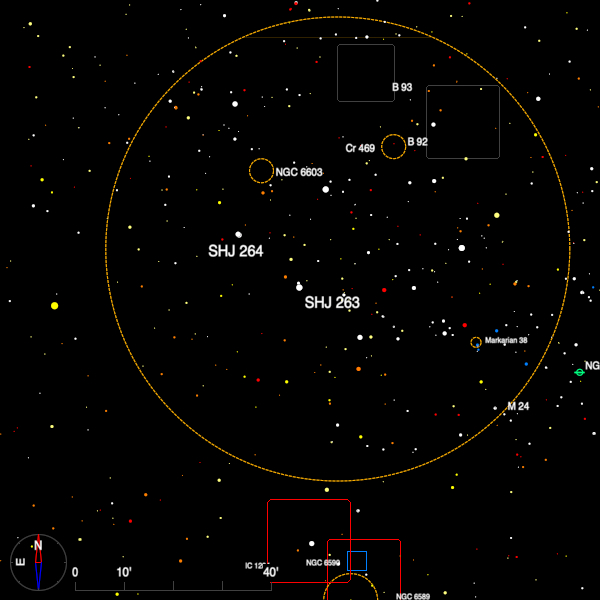

SHJ 263 (18 17 51.13 -18 47 54.6) sits in the yellow area marked Star Cloud M24 in The Cambridge Double Star Atlas, although it is not labelled. It is probably more accurate to define SHJ 263 as a foreground grouping of stars.

The main components are 6.8 and 9.3, separated by 54" in PA 11 degrees. The WDS lists six other companions of magnitude 12 and 13 within 30" of A and B. The only entry in Gaia DR3 for this group is that of the primary star which is given a distance of 1038 light-years whereas the distance of the star cloud as a whole is given as 10,000 light-years in the on-line literature.

A finder chart for the double stars SHJ 263 and SHJ 264 in Sagittarius created with Cartes du Ciel. Twenty minutes NE is SHJ 264 (18 18 43.26 -18 37 10.8) and the bright pair is called AC. These stars are magnitudes 6.9 and 7.6 with a separation of 17" in PA 51 degrees.

S. W. Burnham has added a couple of more difficult tests for 25-cm aperture. A is a close pair, the companion (B) is magnitude 8.2 and only 0".5 distant from A and has moved from PA 155 degrees in 1878 to a current value of 136 degrees. Some years before this, Burnham had noted a 13.1 magnitude star (D) 6" away from C whilst Philip Fox added a 10.8 at 145" from A.

The primary star is a B0Ib supergiant and Gaia DR3 gives distances of 1826 and 4672 light-years respectively for A and B.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

May 2022 - Double Star of the Month

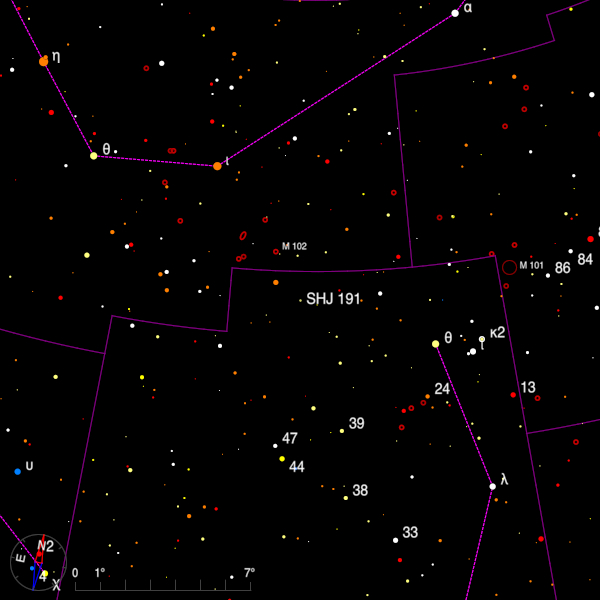

In the second edition of the Cambridge Double Star Atlas, SHJ 191 (14 59 34.58 +53 51 36.7) is the most northerly labelled double star in the constellation of Boötes and lies just over a degree south of the border with Ursa Major.

A finder chart for the double star SHJ 191 in Boötes created with Cartes du Ciel. It was measured by Sir James South on 1823, April 27 and again on May 3 of that year using his 5-foot equatorial and he found the mean separation to be 40".85 (the text in the catalogue gives 48".85) and the mean position angle 343° 10'. These values are little changed today and whilst the proper motions determined by Gaia in the EDR3 catalogue are similar, the parallaxes appear to be significantly different, with 9.590 ± 0.122 mas for the A component and 8.875 ± 0.015 mas for B. The large error for A may indicate additional structure.

The Washington Double Star Catalog (WDS) gives magnitudes of 6.9 and 7.6 for A and B and both stars are F1 dwarfs. An interesting feature in the finder chart plotted using SIMBAD is the presence of a nearby pair of faint red stars and which are described at greater length in the upcoming Double Star Section Circular (DSSC) Number 30.

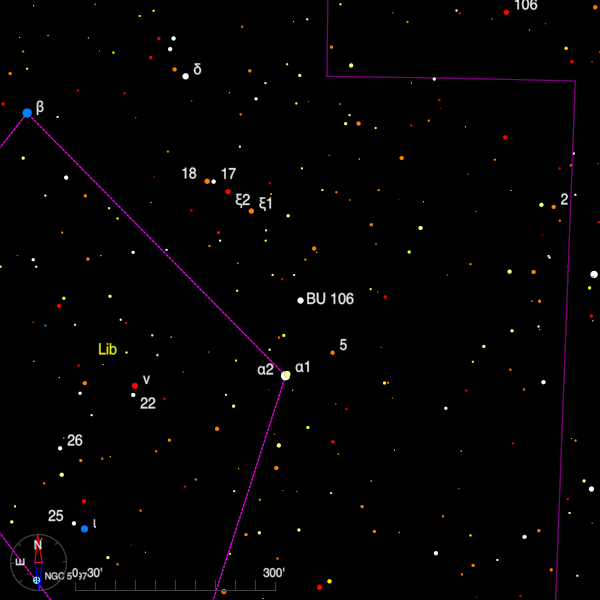

One of S. W. Burnham's more attractive pairs for the small telescope is mu Lib - also known as BU 106 (14 49 19.09 -14 08 56.3). It is easy to find sitting just 2 degrees north and slightly west of Zubenelgenubi, or alpha Cap, which is, in turn, a fine very wide pair, the stars being 376" apart.

A finder chart for the double star BU 106 in Libra created with Cartes du Ciel. Mu Lib was discovered by Burnham with his 6-inch Clark in 1873 when the stars were separated by 1".3, and since then they have slowly separated (currently 1".9) with a change in position angle of just 27 degrees, even so an orbit exists for the system with a period of 614 years. A and B have V magnitudes 5.6 and 6.2 and whilst the A component does not appear in EDR3 the B star has a measured distance of 245 light-years. A magnitude 12.6 star lying at PA 232 degrees and 27" from A has the same parallax and would appear to be physically connected to the binary pair.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

March 2022 - Double Star of the Month

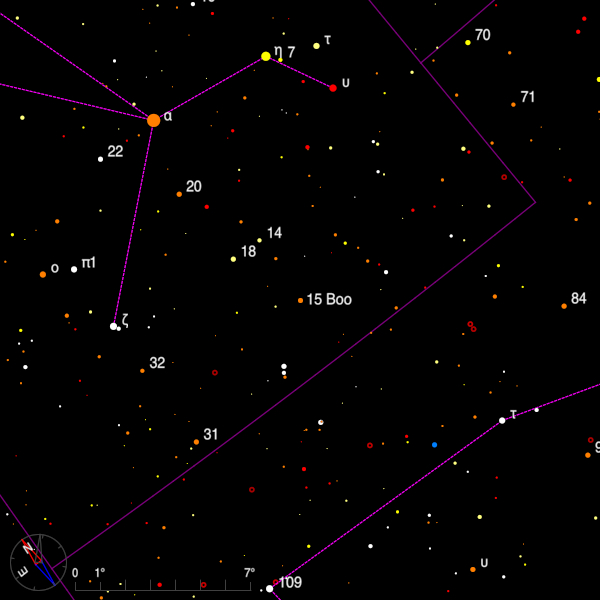

15 Boo (14 14 50.85 +10 06 02.2) is a naked-eye star about 9 degrees due south of Arcturus. Discovered as a close double by Gerard Kuiper in 1936, it has shown little motion since that time. I measured it on 3 nights in 2001 using the 8-inch Cooke refractor at Cambridge and got a relative position of 119 degrees, 1".1. The Washington Double Star Catalog (WDS) indicates that in 2015 the position was 111 degrees and 0".8.

A finder chart for the double star 15 Boötis created with Cartes du Ciel. The difficulty of resolving this pair is exacervated by the difference in magnitude between the components: 5.4 and 8.4. In 2020, Dr. Marco Scardia using the 1-metre Epsilon telescope at the Plateau de Calern near Nice, found that B was itself a close visual pair: 8.4, 10.0, 175 degrees, 0".2.

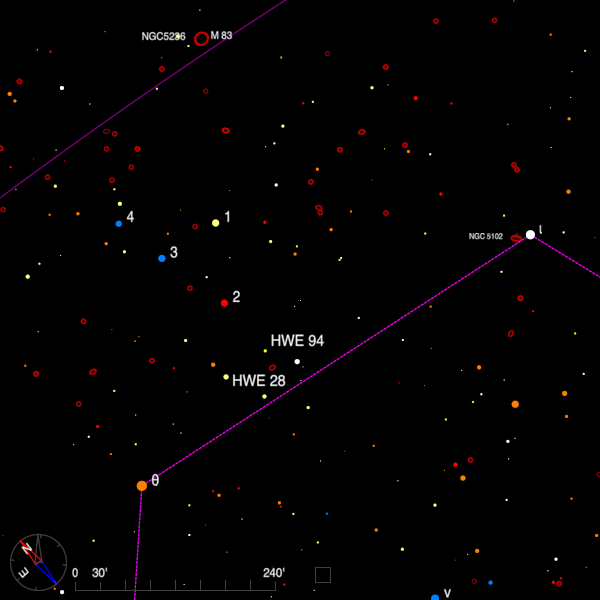

In an area just north of a line drawn between theta and iota Centauri there is a rich profusion of visual double stars. One of the more interesting is HWE 28 (13 53 32.75 -35 39 51.2) a binary whose components shine at magnitudes 6.3 and 6.4. The period is 363 years and at the present time the stars are 1" apart in PA 317 degrees. An 8.7 magnitude star lies 68" away in PA 7 degrees and two much fainter stars can be seen - a 12.3 at 150 degrees 28" and a 14.8 at 133 degrees 38".

A finder chart for the double star double stars HWE 28 and HWE 94 in Centaurus created with Cartes du Ciel. Just 1 degree due west is HWE 94 (13 48 55.07 -35 42 15.1) where the components are 6.6 and 10.2 and the separation 12" in PA 0 degrees. The HWE stars were found by Herbert A Howe, who started his career at Cincinnati Observatory, and went on to become Director of the Chamberlin Observatory which was attached to the University of Denver, Colorado. It boasted a 20-inch Clark refractor.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

May 2021 - Double Star of the Month

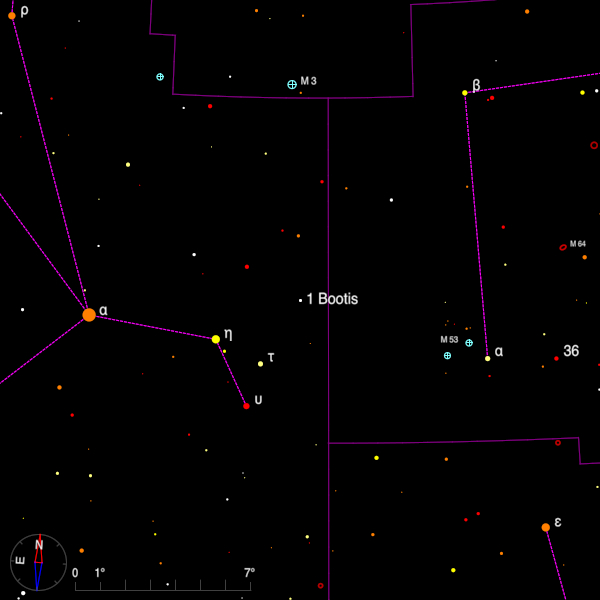

1 Boötis (13 40 40.50 +19 57 20.4) is a star just about visible to the naked eye on a good night. It can be found about 4 degrees WNW of eta Boötis. It is not an easy double star for the small aperture and I have not actually observed it, even thought the primary is a naked-eye object.

A finder chart for the double star 1 Boötis in Boötes created with Cartes du Ciel. The Washington Double Star Catalog (WDS) gives the magnitudes as 5.8 and 9.6 with the current position angle and separation being 133 degrees and 4.4 arc-seconds. A 15-cm aperture should give a good view of the stars, the primary being white - its spectral class is A1V. There is a faint field star, magnnitude 12.2, 88 arc-seconds away whilst the 7.4 magnitude star at 208 arc-seconds has a similar parallax and proper motion as the stars of the binary. According to Gaia EDR3 the three lie at a distance of 310 light-years.

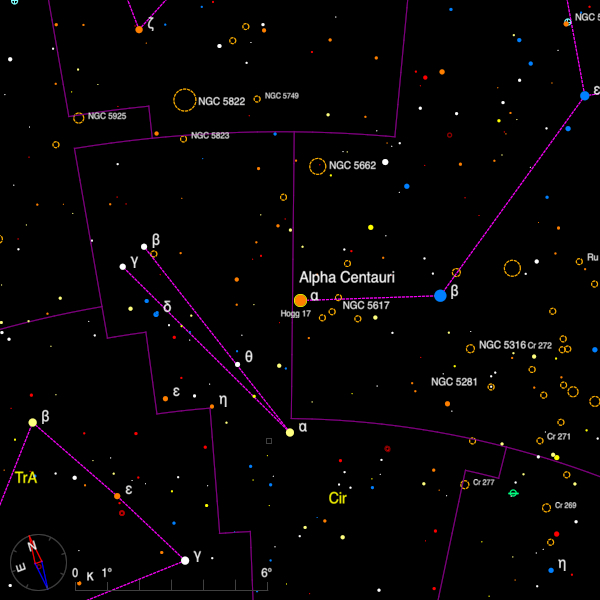

For the first time in this series, (as far as I know, and deliberately at least!) a binary star is going to be included a second time. This is because it is an exceptional object, about which much has been learned recently so it seems a good time to take another look at alpha Centauri (14 39 36.50 -60 50 02.3).

A finder chart for the double star alpha Centauri in Centaurus created with Cartes du Ciel. In May 2007, alpha Cen was at PA 235 degrees and 8".4. This month it can be found at 354 degrees and 6".35, although it is now widening, but only as far as 10".4 in 2020, and then it closes to 1".7 in 2038. Extensive direct imaging has been done of both the stars in the bright binary and the physically connected Proxima Centauri.

To date there definitely seems to be one planet orbiting Proxima and recent observations suggest there is a second one. Both bright components have been suspected of having planetary companions and a recent paper purports to show a candidate close to the A component.

The latest data from the Gaia mission - data release EDR3 - includes a measurement of Proxima Centauri. The satellite finds the star to be 4.2465 light-years away with a quoted error of 0.0003 light-years. The main stars are far too bright to have been considered for data reduction at present though it is hoped that this might be done towards the end of the present mission.

Alpha Centauri is always a 'goto' object for the observer fortunate enough to be south of latitude +20 degrees or so. I have seen the stars in the 67-cm refractor at Johannesburg, and they appear like car headlights - dazzlingly bright.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

May 2020 - Double Star of the Month

Epsilon Boötis (14 44 55.44 +27 04 29.9) is one of the best-loved and most well-known of visual double stars - and one of the brightest - its components are 1.9 and 4.8 in the Gaia G band - the equivalent of Johnson V.

Its spectacular colours prompted F. G. W. Struve to call it Pulcherrima (most beautiful). It was found by William Herschel and was catalogued by him as H I 1. W. H. Smyth calls it pale orange and sea green but leaves any discussion of it out of his book Sidereal Chromatics. Apertures of 15-cm will show it well, especially if a higher magnification is used.

Gaia DR2 includes both components but does not give a parallax for the bright star. The quoted error in the parallax for B is significantly larger than normal, which may be due to the proximity of A or the fact that B is a spectroscopic binary, although it does not appear in the Ninth Spectroscopic Binary catalogue. DR2 makes the distance of B to be 219 ± 6 light-years. The pair appear to be physical with the position angle having increased about 45 degrees to 347 degrees in 2018. The distance at that epoch is 2".8 which has changed little since 1777. Assuming the orbit is circular then the period will be about 2,000 years.

The galactic equator passes through the north-east corner of Ara and close to the very young cluster NGC 6193, which in turn is just east of the HII region NGC 6188. About 1 degree ENE of NGC 6193 is the wide binocular triple star DUN 211 (16 47 28,13 -48 19 10.1).

The brightest pairing (AB) is stars of magnitude 6.5 and 8.1 in the G band of Gaia. The primary is clearly a red star and is a bright M giant whereas the companion 106" distant in PA 125 degrees is early F. The third obvious component can be found at 144 degrees and 130" and has G = 8.1. However, 10-cm aperture should be sufficient to show the close companion to C found by John Herschel at the Cape (HJ 4885). D is 3".8 away in PA 239 degrees, and both C and D have similar parallaxes and proper motions. Gaia DR2 puts them at around 440 light-years. Star B is unconnected and star A is much more distant than its companions.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

June 2019 - Double Star of the Month

This month's choices are both fine sights in small telescopes but also of great interest to enthusiasts of stellar multiplicity.

Mu Boötis (15 24 29.54 +37 22 37.1) was noted as a very wide pair by William Herschel in 1780 when he gave a distance of 2' and 8" ("exact est.") for AB. When he revisited the star a year later he noted the secondary was itself a close double (BC) which became H I 17 in his first catalogue. The modern orbit for this pair which suggests a period of 265 years which gives a separation close to 2".1 for 1781 so its odd that Herschel did not see the two stars in 1780.

The distance of AB given by Herschel must be a transcription error as the three stars have common proper motion and there has been little relative change over the last 240 years. During the middle of the C19 the separation closed to less than 0".5 since when it has been widening. For the summer of 2019 the stars can be found at 3 degrees and 2".2, an easy split for 10-cm, as the stars are mags 7.1 and 7.6.

In 1988 using the CFHT on Hawaii, the CHARA team led by H. McAlister found that A was also a close pair whose separation varied between 0".06 and 0".12 in a period of 3.75 years. Although the four stars may seem to be physically connected the astronomer Olga Kiyaeva speculates that because of elemental abundance differences what we are seeing is the close passage of two unassociated pairs.

Gaia DR2 puts A at 116.1 light years but with an uncertainty of 2.4 light years, no doubt due to the interferometric companion, whilst BC are at 120.0 light years with an uncertainty around 0.3 light years.

One of the few constellations which has not yet been visited in this series is Apus, which lies between Pavo and Musca and whose southern border impinges on the northern edge of Octans at the South Celestial Pole.

Perhaps the best pair is I 236 (14 53 13.57 -73 11 24.3) in which the stars are visual magnitude 5.9 and 7.6 and they are currently separated by about 2".2 in PA 123 degrees. In fact there have been no measures since 1996, but there is intriguing evidence that this may be a binary pair with a highly inclined orbit.

Innes, in his Southern Double Star Catalogue of 1927 notes that the first observation was made by Pickering in 1891 in which he estimates a separation of 0".6. Innes independently noted the pair during his early double star searches but Pickering's report to Astronomische Nachrichten at the time mentions only that the primary star had two companions within 30 arc-seconds, and this prompted Innes to claim the close pair for himself.

Just 7 degrees due north is the binary pair HJ 4707. Orbiting in 346 years these stars are currently 1".3 apart in PA 266 degrees, and the magnitudes are 7.5 and 8.0.

Very fine

was John Herschel's comment when he found the pair in April 1835.Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

May 2018 - Double Star of the Month

Not far from Arcturus in the Spring sky is pi Boötis (14 40 43.56 +16 24 05.9) a beautiful pair of white stars found by Christian Mayer and later called H III 8 by William Herschel and STF1864 by F. G. W. Struve. The stars are magnitudes 4.9 and 5.8 and have shown little motion since discovery. Smyth, Webb, Sissy Haas and me all find the both stars are white and the spectral type are B9 and A6.

The primary star, at least, is over 300 light years away but the quoted error on the Hipparcos parallax is significantly large and is probably not affected by the presence of the visual secondary. In 1984 the primary was found to be a spectroscopic binary and the Washington Double Star (WDS) Catalog notes that the secondary is also a spectroscopic binary. In 2015 I found the stars at 113 degrees and 5".4 apart.

The upcoming Gaia catalogue may well settle the issue of whether the visual pair is physical, and if it is then we have here a quadruple system. A third star of mag 10.6, first noted in 1881 is 163 degrees and 127" distant.

k (not kappa) Lupi (15 25 20.21 -38 44 01.0) is a magnitude 4.6 star located in central Lupus about 2 degrees north of delta.

It was observed by James Dunlop who noted a couple of distant 9th magnitude companions. Dunlop's original paper reads for entry number 183:

A star of the 6th mag with two stars of the 10th

and the measured separations are 12 and 15". It's possible that Dunlop meant 120 and 150" as the latest WDS positions (for 2016 and 1999, respectively) are 203 degrees and 93" for AB and 134 degrees and 149" for AD.In 1896 Robert Innes, observing from Cape Town using a 7-inch refractor, found that the B component was an almost equal double (I 87) at a distance of 1".4 since which time the position angle has reduced by 40 degrees to 207 degrees and the separation is now just below 1". The relative faintness of the two stars means that this is now a stiff test for 25-cm aperture. Innes also added a magnitude 11.5 at 17 degrees and 42".

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - June 2013

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

Situated in the north of Boötes, STT 298 (15 36 02.59 +39 48 08.7) is one of the more rapid binary systems found by Otto Struve at Pulkovo and it now embarking on its fourth orbit since discovery. Look for the naked-eye pair nu1 and nu2 Boötis some 6° following beta Boötis and STT 298 can be found just south preceding phi Boötis. The star is nearby (the distance is 73 light years) so the orbit is relatively large in angular terms. The stars are almost near peristron and at 182°, 1".18 in mid-2013 they offer a good opportunity to see a pair with a period of only 55.6 years. The system moves across the sky at almost 0".5 per year and is accompanied at a distance of 121" by star C which is mag 7.8 and also a K dwarf. For the telescopic observer there are two fainter but unrelated stars of mags 12.1 and 13.9.

DUN 178 (15 11 34.82 -45 16 39.0) is an orange KOIII giant star of mag 6.3 accompanied at a distance of 30".6 by a mag 7.3 white star according to Richard Jaworski using a 100-mm aperture in Australia. Both these stars appear in the Hipparcos catalogue but do not appear to be connected in any way. A is 510 light years away whilst B is 400 light years distant. At discovery in 1826 the pair were separated by 40" so the change is purely due to different proper motions. This pair is located in the heart of Lupus, a constellation rich in visual double stars, and can be found in the same low-power field as lambda Lupi. In 1929 Willem van den Bos, using the 26.5-inch refractor in Johannesburg, found a companion of mag 9.6 some 1".1 distant from A. There has been little change in the position of this star in the intervening 80 years and it offers a challenge to a 30-cm telescope in a good location.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - May 2013

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

There are two pairs for the price on one in the northern half of this month's column. In the extreme north-west of Boötes following eta UMa is a coarse group of bright stars. The two closest together are kappa and iota and both are worth seeking out with telescopic aperture. Kappa Boötis (14 13 29.00 +51 47 23.8) is a long period visual binary with both stars possessing the same proper motion and at a similar distance from us (162 light years). There has been little motion over the past 200 years beyond a slight widening of the separation to 13".6 and a small diminution in the position angle. In 1850 T. W. Webb made the stars pale yellow and bluish whilst in 1915 William Franks recorded yellow and purple. B is a spectroscopic binary with a period of about 5 years. More recently Tokovinin has recorded a 16.9 mag comes at 108" to A which appears to have shared proper motion with AB. Some 25 arc mins south following is iota Boötis (STFA 26 - 14 16 10.07 +51 22 01.3) which is a binocular pair which will benefit from telescopic aperture. The stars are mags 4.8 and 7.4 and are 38" apart. The Irish amateur, Isaac Ward, who used a 4.3-inch Wray refractor, found a comes of mag 12.6 at 92". The spectral types are A7 and K0 and Webb found whitish yellow and lilac.

When William Herschel was accumulating his catalogue of double stars he searched every part of the sky and he must have had a good southern horizon. One of the lowest of his finds is Y Cen (13 53 32.75 -35 39 51.2) which at -35 degs could only have been a mere 5 degrees above his horizon even at culmination. He acknowledges that the pair is `too low for accuracy' giving a distance of 54" (currently 68"). The stars are mags 5.5 and 8.7 and it’s not surprising that Herschel missed the duplicity of the primary, later found by Howe. Currently at 1".0 it was nearer 0".7 in the 1780's but as the two components are almost equal it is a fine object for 15-cm at a suitable latitude. The period appears to be 258 years and the position angle is increasing. Burnham and Innes respectively added fainter companions - 12.3 at 28" and 14.8 at 38". Hipparcos puts the system at 167 light years.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - May 2012

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

Nine degrees south of Arcturus is 15 Boo - a naked eye star which is a difficult double star for the small aperture but which can be well seen in a 20-cm OG on a good night. Track another 3 degrees south-east and the eye alights on a crooked line of 3 stars with the brightest of them being the most northerly. This star is STF1835 (14 23 22.74 +08 26 47.8) and because it is almost half a magnitude brighter than 15 Boo it is unusual in that it has no Bayer number or Flamsteed letter. For the small telescope the pair offers a very pleasing sight with an AO primary being accompanied by an F2 secondary some 6" away to the south. Hartung makes the colours white and deep yellow, Sissy Haas has goldish-white and powder blue whilst W. S. Franks in 1916 made them white and lilac. Angular change has amounted to 7 degrees in the last 230 years but it seems certain that the two stars are physically connected. In 1889 Burnham found that B was a close double (BU 1111) and indeed it turns out to have a binary period of 40 years. The separation ranges from 0".15 to 0".3 so could be seen in 30-cm or more when at its widest in 2022. For 2012.0 the distance is 0".2.

About 3 degrees following beta Crucis, although actually in Centaurus, is a group of bright double stars - R 213, I 424 and CorO 152 - the latter two of which are in the same field. I 424 (13 12 187.63 -59 55 13.9) is a very unequal and rather close pair which needs 20-cm on a good night to see well, but which Hartung could just catch with 10.5-cm. The magnitudes are 4.8 and 8.4 and a recent measure in 2008 by the writer put the fainter star at 13° and 2".0. For the larger aperture, the primary is the binary See 170 - discovered by Thomas Jefferson See and which is only 0".22 apart in mid-2012. This 27 year pair has components of 5.3 and 6.0. Hartung notes that the primary star is yellowish but it has the spectrum of a B5 dwarf. Some distance from AB-C are two faint companions of magnitudes 12.6 and 14.9. About 8' NE is CorO152 - a 25" pair with colours of orange and reddish according to Hartung. R213 is a pair of white stars of magnitude 6.6 and 7.0 which has moved little in PA since discovery by Russell but the separation has tripled to 0".9 and this makes it an excellent test object for a 12-cm aperture.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - May 2011

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

STT 288 (14 53 23.35 +15 42 18.7) can be found about 3.5 degrees due south of xi Boötis as a star just below the usual limit of naked-eye visibility. The components are magnitudes 6.9 and 7.5 and revolve around one another in about 313 years. About 100 years ago, the Greenwich Observatory observer William Bowyer considered the two stars were optical in nature. To him they appeared to be steadily increasing in separation since discovery in 1845 when Otto Struve found them separated by 0".45. A few years after Bowyer's observation, the stars began to slowly close again. The orbit is fairly eccentric and the stars will continue to close to 0".51 in about 50 years time. Hipparcos places them at a distance of 155 light years. In the meantime at PA 160°, 1".06 they form an excellent test for the 10-cm aperture.

Lupus is full of fine pairs and this column regularly features stars in that southern constellation. This month is the turn of Kappa Lupi = Dunlop 177 (15 11 56.07 -48 44 16.2), a beautiful pair of pale yellow stars according to E J Hartung. More recently Richard Jaworski notes them as yellow-white and plain white whilst the WDS gives the spectral types as B9.5V and A5V whilst the brightnesses are listed as 3.8 and 5.8. To the small aperture this is one of the easiest and brightest pairs in the sky - the current separation is 26".2 and this has decreased about 3" since 1826. With very similar proper motions, it is highly likely that the stars form a binary system, but Hipparcos has had some trouble in deciding the distance of the fainter component.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - June 2009

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

The two pairs in this month's column are similar in that they contain stars of spectral type A but there the similarity ends. Zeta Boötis is a close, bright binary and SHJ 179 is much fainter and considerably wider.

zeta Boötis (14 41 08.92 +13 43 42.0) is a white mag. 3.7 star south following Arcturus by about 8 degrees. Its binary nature was discovered by William Herschel on 1796, Apr 5 when he said that the pair was `very nearly in contact; I can, however, see a small division'. He had previously seen a mag. 11 optical companion in 1782 which became H VI 104. The proper motion of AB is taking it away from C and the distance has increased from 99 to 103 arc seconds over the last century or so.

The main pair is a bright, equal binary of high inclination and extreme eccentricity - in fact it appears to be the current record holder, surpassing even the value for 41 Dra (see Astronomy Now for June 2009). Having spent most of the last half century near PA 310 degrees and separation 1", it is now noticeably closing and the writer found it separated by 0".6 last Spring. If the 122.98 year orbit by Andreas Alzner is correct it will pass 0".5 in 2011 and then dip below 0".01 in the summer of 2021 when the angular motion will be 10 degrees per DAY. From there it will rapidly return to the 4th quadrant again the following year. The stars are both A0 dwarfs and the revised Hipparcos parallax is 19.00 mas.

SHJ 179 (14 25 29.91 -19 58 11.8) First measured in 1798 and placed in the catalogue of stars found by James South and John Herschel, this attractive wide pair of magnitude 6.6 and 7.2 stars makes an excellent target for the small telescope. Sissy Haas marks them as reddish white whilst Hartung from Australia notes them as pale yellow. They are low in the sky for the northern observer so this may explain the reddish tinge, as the WDS gives the spectral types as A2V and A4V. The proper motion of A seems to be shared by B and the relative position has changed little in the last 200 years, the current values being 205 degrees and 34.7. These are distant stars, the parallax of A placing it about 457 light years away.

In 1867 Burnham using his 6-inch Clark refractor found that B was double again and in the intervening period, the companion has moved about 15 degrees in a retrograde direction, remaining close to the discovery separation of 1".2. This pair is BU 225 BC in the WDS but also bears the appellation HDO 138 indicating that it was found later from Peru by the Harvard observers at Arequipa but who were unaware of Burnham's observation. The difference in magnitude is about 1.7 so this pair requires at least 100-mm of aperture to see well.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - June 2008

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

The two systems this month are both bright and relatively easy objects to see in small telescopes now but both have highly eccentric orbits resulting in large ranges of apparent separation during the orbital cycle.

The apparent orbit of 44 Boötis (STF 1909 - 15 03 47.68 +47 39 14.5) is a very elongated ellipse with the primary star somewhat nearer the eastern end than the western end. At

present the companion is perched at the eastern end of the ellipse having been virtually stationary for the last few years. It will soon be closing noticeably and accelerating to pass by the primary at a distance of 0.20 arc seconds in 2019. At this point the angular motion will be very pronounced - more than 1 degree per week. The pair was discovered by Herschel in 1781 at PA 60.1 degrees but he made no note of the separation. A measure made a few weeks ago (i.e. early July 2008) showed the companion to be at precisely 60.0 degrees.

The current orbit by Soderhjelm gives a period of 206 years. The stars are F7 and K4 dwarfs and the visual magnitudes 5.20 and 6.10. The secondary is one of the brightest W UMa eclipsing systems known with a period of 6 hours.

xi Sco (16 04 21.63 -11 22 24.8) was found to be triple by Herschel the year after he found 44 Boo. The wide pair was separated by about 6.7 arc seconds and since then the angle has decreased 50 degrees and the separation has increased somewhat. Herschel gave no separation for AB - although his measure for PA put the pair at 188 degrees. In Lewis' book (1906) several orbits were listed, all of them with a period near 100 years and very low eccentricity. However, the equality in brightness of the two stars led to differences of 180 degrees in some position angles and it was left to Aitken to show that the period was nearer 45 years and was highly eccentric. The currently accepted period is 45.9 years and the is pair is now approaching maximum distance (1.13 arc seconds in 2021) so this is a good chance to see it with 15-cm aperture. xi Sco is missing from the Hipparcos catalogue but it is still possible to estimate its distance because it shares a common proper motion and radial velocity with the 12 arc second pair STF1999 some 5 arc minutes SE so that the whole system is quintuple. STF1999 has a parallax of 33 mas but with a significant uncertainty. The WDS gives magnitudes of 5.16, 4.87, and 7.3 for the three stars of xi Sco.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - May 2008

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

Both binaries in this months notes had orbits calculated for them about 20 years ago by Wulff Heintz, a great visual observer who died on June 10, 2006 after more than 50 years of observational activity. The orbits remain in the catalogue.

Located in the western part of Boötes, STF1785 (13 49 0.28 +26 58 48.5) is a rather faint (mags 7.4 and 8.1) but attractive pair of orange K-type dwarf stars, discovered by Sir James South in 1823. The system is located fairly near the Sun at a distance of about 45 light years. The predicted position for mid-2008 is 179o.9, 3".13 but recent measures by the writer seem to indicate that the position angle is about 3 degrees smaller than this possibly suggesting that the 155.75 year period is a little short.

Lupus is a bright constellation located halfway between the head of Scorpio and alpha and beta Centauri and it contains some beautiful pairs for telescopes of all apertures. Gamma Lupi, (15 35 08.46 -41 10 00.1) a brilliant white binary whose primary is a distant B subgiant has a highly inclined orbit of 190 years period and at times of closest approach the two

components are only 0.07 arc seconds apart as happened in 1930. The stars of apparent magnitude 2.95 and 4.45 are currently almost at maximum separation (0".83 in 2013) so see them whilst you can. Fortunately this pair was near widest separation when found by John Herschel from the Cape in 1835.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director

-

Double Star of the Month - May 2007

In this series of short articles, a double star in both the northern and southern hemispheres will be highlighted for observation with small telescopes, with new objects being selected for each month.

xi Boo (14 51 23.3 +19 06 02) was discovered by Herschel the elder on 1780, Apr 9 with the note "Double L. (large star) pale r. or nearly r. S. (small star) garnet, or deeper r. than the other" (my brackets). With a parallax of 0".149 it is a nearby system and so the large apparent orbit means that for most of the 151 year orbit the pair is well within range of the small telescope. It is also a beautiful pair - the colours are yellow and orange, but unequally bright, the apparent V magnitudes being 4.76 and 6.95. The stars are presently closing slowly and in mid-2007 there are to be found at PA 311 degrees and separation 6".2. Closest approach occurs in 2066 when the stars are barely 2" apart. The WDS lists 1351 measurements of this pair and only 432 for alpha Centauri - a measure of how much the southern hemisphere is missing its double star observers.

alpha Centauri (14 39 40.9 -60 50 07) is the nearest binary star to the Sun and the most spectacular visual system in the sky. Discovered by Father Richaud from Pondicherry in 1689 whilst observing a comet ("je remarquai que le pied le plus oriental & le plus brillant etoit un double etoile aussi bien que le pied de la Croissade - I noted that the brightest star at the easternmost foot (of Centaurus) was a double star as good as that at the foot of the Cross" i.e. alpha Crucis.

In 1838 Henderson first measured the parallax at about 1 arc second but it was left to Bessel to publish the parallax of 61 Cygni first. A modern value obtained by the Hipparcos satellite (0".74212) is equivalent to 4.395 light years with a formal error of 0.008 light years. The stars are yellowish and orange-yellow reflecting the spectral types of G2V and K1V and the orbital period is 80 years. Because the system is so close the apparent separation of the orbit varies from 1.7 to 21.7 arc seconds so that they can be seen by small telescopes throughout the orbital cycle. At present the stars are closing (235 degrees and 8".67 for 2007.5). In 1915, Robert Innes found a third star of V=11 some 150 arc minutes away which shares the proper motion of alpha but which has a slightly larger parallax. The star became known as Proxima Centauri and is our nearest stellar neighbour. In 2006, a search was made in the infra-red around alpha Cen B using adaptive optics on one of the VLT telescopes. The modelled mass for this star is about 0.027 solar mass less than that derived from the orbit and it was thought that this might be explained by the presence of a sub-stellar object circling B. In all 252 faint background stars were found within 15" of alpha Cen B but nothing co-moving and therefore nothing physically connected to B itself.

Bob Argyle - Double Star Section Director